Ancient Handprints and Hidden Symbols: Tataouine's Abandoned World Pt. 3

Fingerprints of history pressed into forgotten walls

The Mysterious Symbols of Beni Khedache

Leaving Chenini behind, we faced a choice about our day's final destination. According to our schedule (which had gradually transformed from a rigid itinerary into more of a loose suggestion), we should have headed directly toward our evening's accommodation. But I'd come across intriguing references to mysterious ancient symbols carved into troglodyte dwellings in the nearby village of Beni Khedache, and the amateur art historian in me couldn't resist the detour.

"Just one more stop," I pleaded as my aunt consulted her watch with the concern of someone who had experienced my uncle's sunset photography delays many times before. "There are these symbols no one can explain..."

The mention of unexplained archaeological mysteries proved persuasive, and soon we were navigating toward Beni Khedache along roads that grew progressively narrower and less maintained.

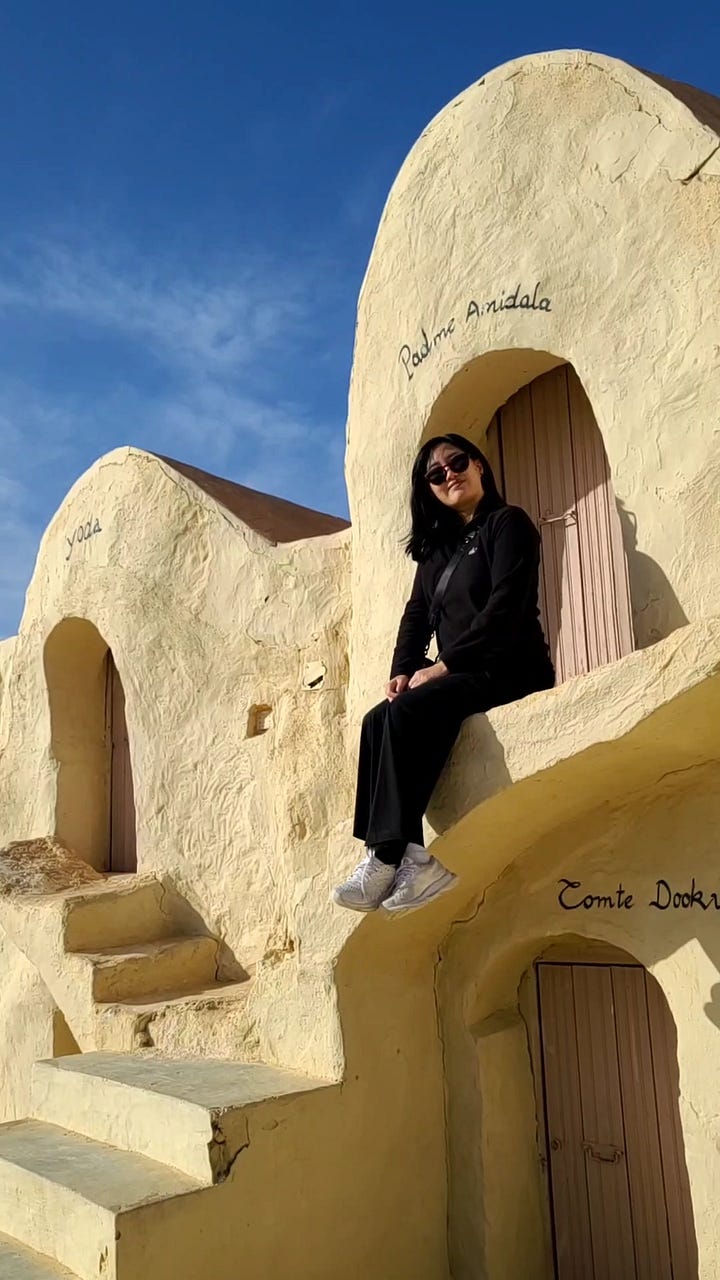

What greeted us upon arrival was a study in cultural collision: a row of domed troglodyte structures facing what appeared to be an abandoned village spread across a barren hillside, the beige-hued buildings blending almost seamlessly with the surrounding landscape. Nearby stood a hotel complex with Star Wars character names on its doors, and a café with Chewbacca-themed decorations—another outpost of the sci-fi tourism that had spread across Tunisia's southern reaches.

The men lounging at the café watched our arrival with the mild interest of people who had seen tourists before but not in great enough numbers to become indifferent to them. We approached with our now-familiar linguistic patchwork—fragments of English stitched together with basic French and rudimentary Arabic greetings. My attempts to explain what we were seeking met with blank looks until I sketched some wavy lines and fish shapes in the air. This universal language of drawing succeeded where words had failed, triggering a spark of recognition.

After a brief consultation among themselves, one of the men gestured for us to follow. He led us past the main tourist areas to what appeared to be abandoned residential sections of the troglodyte complex, eventually procuring a large key to unlock a wooden door that showed few signs of regular use.

As we stepped inside and our eyes adjusted to the dim interior, the reason for the door's security measures became apparent. The walls and ceiling were covered in a mesmerizing array of raised patterns—abstract geometric designs, zigzagging lines, and what appeared to be aquatic shapes. What made these markings truly extraordinary wasn't just their age or meaning, but the method of their creation. Unlike carvings or paintings, these designs protruded from the surface in bas relief, as if they had been pushed outward from within the solid stone.

I ran my fingers over the patterns, feeling their subtle elevation from the surrounding surface. These weren't simple etchings or paintings; they had dimensionality that defied easy explanation. The symbols included complex geometric compositions with lines arranged in parallel formations, dotted patterns forming curved shapes, and what resembled winding rivers or perhaps serpents.

Our guide, watching us from the doorway and recognizing our awe, indicated that there were more to see. Communication was conducted more through gesture than shared vocabulary.

At the second dwelling around the corner, a similarly unassuming exterior gave way to an even more elaborate collection of symbols. I found what looked like animal shapes and spirals, feeling like I was seeing a message in a bottle that had washed up from another century. My inner archaeology nerd was having a field day, while the practical part of my brain (the one responsible for remembering hotel check-out times and avoiding tourist scams) kept wondering what these symbols meant to the people who made them, and whether my interpretations would be as hilariously off-base as future archaeologists examining our emoji use might be.

Most remarkable of all were the handprints we discovered in the third dwelling. Unlike the abstract patterns, these were unmistakably human—perfect impressions of palms and fingers pressed into the surfaces above doorway arches and along walls. The preservation was so detailed I could see individual fingerprints, frozen in time like a prehistoric police blotter. Unlike the painted handprints you typically see in caves around the world (where someone essentially flashed a peace sign and spray-painted around it), these had actual dimension and texture.

We moved between these hidden galleries with growing fascination, photographing each new discovery. The silence was profound—no tour guide's rehearsed explanation, no informational placards, not even names for what we were seeing. Just us, these ancient marks, and questions hanging in the air: Who made them? What did they mean? How were they created?

Our guide merely shrugged and smiled when asked about their meaning. The only available information came from scattered online sources with unverified claims about their possible age and significance. Some suggested connections to early Christianity through the fish symbols, others to older shamanistic practices through the handprints. The dating remained equally ambiguous, with estimates spanning several centuries.

Standing in these cool, dim spaces surrounded by ancient impressions, I felt a profound sense of connection across time. These weren't simply curious markings but potential windows into an indigenous knowledge system that developed in response to this specific landscape. The symbols might record astronomical observations, territorial boundaries, cultural stories, or spiritual practices we can barely glimpse. What's certain is that they represent an intellectual tradition unique to this region and people—one that deserves study through collaborative approaches that center Amazigh perspectives rather than imposing external interpretations. These handprints and patterns remain eloquent even in their silence, reminding us that human creativity and communication have flourished in this challenging environment for millennia, and continue to do so through the living cultural practices of contemporary communities.

Before leaving, I paused at one last handprint preserved above a doorway. The impression captured such subtle details that I held my own hand next to it and wondered about its creator. My palm didn't quite match—either I had evolved significantly larger hands than my ancestors, or more likely, I was comparing myself to someone with a different genetic makeup entirely. It was like finding a perfect fossil of a moment—someone pressing their hand into soft clay that somehow hardened into permanence while empires rose and fell, technologies emerged and became obsolete, and tourists like me eventually came poking around with smartphones and sunscreen.

The anthropological mystery sparked my imagination. These weren't simply curious markings but potential windows into lost ways of understanding the world—research waiting to happen, connections to be traced between these symbols and similar ones across North Africa. Perhaps even insights about knowledge transmission in cultures without written language.

But this mystery would have to remain unsolved for now. The sun had begun its descent, and hours of driving lay ahead before reaching our next destination. With reluctance, I followed my family back to our car, carrying away more questions than when we'd arrived.

The Journey to Hammamet

As afternoon light softened toward evening, we left Beni Khedache behind and began the long drive to Hammamet. 5 hours stretched before us—a journey that would carry us from the rugged interior back to the Mediterranean coast, from ancient Amazigh settlements to the tourist-filled beaches and resorts of Tunisia's coastal playground.

The conversation inside our car ebbed and flowed between excited recollections and comfortable silences filled only with the sound of tires on pavement. The symbols in Beni Khedache presented a sobering reality: knowledge can be lost entirely, meanings forgotten, connections severed. Those handprints and geometric patterns now existed primarily as aesthetic curiosities, their original purpose faded beyond recovery.

As modern development increased around us near the coast, I questioned the proper response to witnessing the twilight of ancient knowledge systems. Is documenting vanishing cultures enough? Or does true respect require something more active—advocacy for climate justice, support for language preservation, recognition of indigenous land and water rights?

Night had settled by the time we reached Iberostar Hammamet, where security procedures rivaling those at Hilton Monastir greeted our arrival. At the reception desk, the staff mercifully suggested we complete check-in after dinner—my aunt's hurry to make the "free" half-board meal now vindicated. We headed straight to the enormous buffet hall, our dust-covered clothes standing in stark contrast to the cruise passengers from Norway in their resort wear. After piling plates with everything that looked appetizing, we ate with the particular hunger that comes from a day spent in historical exploration.

Check-in complete and adjoining rooms secured, we finally surrendered to the luxury of hot showers that washed away layers of desert. As exhaustion overtook us, we drifted to sleep with balcony doors cracked open, the invisible Mediterranean sending its rhythmic sounds through the darkness—a gentle reminder that Tunisia's contrasts extend from desert to sea, from ancient wisdom to modern tourism, from cultural treasures to all-inclusive comforts.

Carrying Amazigh wisdom to resort pillows,

Susie